oral design

oral design

“oral design” stems from Geller's pride in the dental technician profession and our awareness that we are one of the beloved dental technicians. To put it bluntly, without fear of misunderstanding, the motivation for adopting this name “oral design” was also a kind of historical “revenge” against the dental world. It is a “payback” against the conservative systems within the dental world that have placed us in an oppressed position within our relationship with our partners, the dentists.

However, it is not about revenge against dentists or anything like that. It is closer to a desire to restore the dental technician to their true form, to make people aware of the existence of the dental technician.

Dental technicians from generations before Geller were completely in the shadows (this tendency still exists depending on the country and generation).Typically, patients visit dental clinics and only interact with dentists. They often don't even know the profession of dental technician exists.Therefore, Geller believed it was time to define the work of dental technicians, and he defined it as “oral design.”Initially, Geller did not intend to organize this group; he defined “oral design” solely to raise public awareness of our profession as dental technicians.

“Dentists typically just fit what we make. I believe it is us dental technicians who create things, who do the creative work. We are the designers.”

Willi Geller

While working as a dental technician, Geller encountered a question.

When we go to a beauty salon, the stylist listens to our requests, examines and assesses the shape of our head and hair texture, accepts the customer's wishes, and naturally creates a hairstyle suited to our facial features as part of their job.

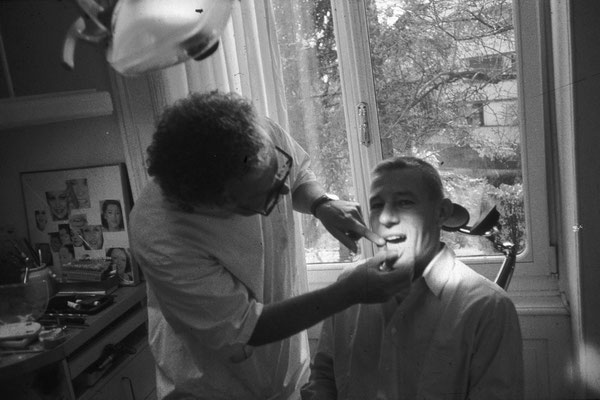

In contrast, our work at that time as dental technicians was merely to receive patient models sent from dentists to the laboratory and mechanically fabricate prosthetics based solely on paper instructions.

In 1982, Geller strongly questioned this conservative, mechanical approach in dentistry. He believed dental technicians should also interact with patients, creating prosthetics and aesthetic dentistry tailored to each patient's facial features, mouth, and individuality. He coined the term “oral design” to encompass these ideas, intending it to challenge the conservative status quo in dentistry.

However, gaining understanding for this proposal at the time was truly no easy task. Geller refused to yield to the conservative barriers within the dental world and persistently challenged dental professionals with the question: “What constitutes a good prosthesis!?”

Today, the reason patients visit dental laboratories for our dental technology work stems from the inception of his “oral design” concept, which he began advocating in 1982. Dental technicians worldwide, along with other dental professionals, have benefited significantly from his actions. Prior to this, dentists deliberately avoided contact between patients and technicians*1. This was not only a Swiss custom but a global dental convention, and it remains a persistent practice worldwide.

However, Geller recognized and advocated early on the necessity of patient involvement to achieve harmonious color reproduction, facial aesthetics, and prosthetic reconstruction tailored to the patient's mouth.

As an aside, around 1990 in Japan—a country relatively advanced in dental technology at the time—there was serious debate over whether shade taking should be performed by dental technicians, whether it was acceptable for them to do it, or whether it should be done by dentists. Japan was still very much in a conservative era.

Even now, the uniquely conservative aspects of dentistry persist in the Asian dental world, and improvements—including in pricing—have not been made.

*1.

The reasons why dentists might deliberately avoid having patients interact with dental technicians include:

1). Due to their educational background, dental technicians are not considered to be in a position to stand before patients.

2). Dental technicians, being behind-the-scenes workers, did not wear clothing that conveyed a sense of cleanliness or was appropriate for appearing before patients.

3). If there were deficiencies in the dentist's treatment, the dental technician might potentially inform the patient about them.

4). Dentists did not want patients to know about the relatively low cost of the technician's work within the overall treatment fees.

5). Dentists were unaware of the work that dental technicians should perform and the importance of dental technicians' skills.

These factors are conceivable. These views held by dentists have not changed significantly even in modern times.

PETER SCHAERER PROF. EM. DR. MED. DENT., M.S.

Willi Geller

However, it was not at all easy for Geller to establish the definition of “oral design.”

When Geller presented his philosophy of aesthetic dentistry to Professor Peter Schärer, then a professor at the University of Zurich, Professor Schärer was completely unresponsive to his proposal.

Geller appealed to Professor Schärer that he could not perform work on university patients without intraoral try-ins of prostheses. It was unclear whether Professor Schärer failed to grasp the necessity or, even if he understood, simply did not wish to delegate this task to the dental technician.

Nevertheless, the debate over dental technicians' presence during patient procedures persisted.(At that time, dental treatment involved a performance where dentists would finish the procedure by modifying the shape of delivered ceramic crowns in the patient's mouth, regardless of the prosthesis's initial form. In short, it was a foolish performance designed to satisfy patients by implying dentists were more talented than dental technicians.)

However, reconciliation was achieved when Professor Schärer subsequently agreed to in-lab try-ins.

This was only natural when considering the patient's best interests and the true essence of aesthetic dentistry. With dental technicians present for the patient, the quality of dental technology improved, leaving Professor Schärer unable to say “NO” and forcing him to accept Geller's proposal. Geller had won back the true role of the dental technician.

This was the “Oral Design” he advocated.

Here again, when the professor gave lectures on aesthetic dentistry, he stunned the world by presenting cases of patients fitted with Geller's metal ceramics. These aesthetically pleasing, lifelike metal ceramics became a powerful tool for the professor, serving as a compelling argument to persuade other dentists.

The impact on the audience during a lecture differs greatly depending on whether the prosthesis is good or not. The audience would have leaned forward to listen intently to the theories advocated by Dr. Peter Schärer. Through this, Dr. Peter Schärer must have felt firsthand the necessity of the dental technician's expertise.

As an aside, this occurred during a porcelain crown placement for the maxillary anterior region (the six front teeth?) at the dentist's office, where Geller was present during the fitting. Geller determined that the prosthesis harmonized with the patient's smile line and overall facial aesthetics. However, the patient complained that the central incisors were too long. The dentist who routinely worked with Geller, acting from the treatment side (the dentist and dental technician's perspective), failed to adequately explain the prosthesis design. Instead, he took the patient's side and criticized Geller regarding the length of the prosthesis's incisal edge. It is said that Geller became so enraged by this that he removed the prosthesis from the patient's mouth, threw it on the floor, crushed it underfoot, and left the dental office.

In another case, he similarly attends the fitting of a set of upper front teeth at the dental office. The patient is delighted and pleased with the prosthesis he created. The dentist is also satisfied with it. Geller presents the dentist with the laboratory fee for this work. However, the dentist tells Geller he cannot afford such a high fee. So, Geller asks the patient, “Then, I will remove this prosthesis and take it back with me. Is that acceptable?” Of course, the patient would never say “Yes.” Seeing this, the dentist had no choice but to pay Geller the legitimate laboratory fee. In this way, Geller fought behind the scenes to establish the status of dental technicians.

Subsequently, Professor Schärer accepted Willy Geller as an honorary member of the European Academy of Esthetic Dentistry (EAED). This marked a significant moment where a dentist recognized a dental technician, a remarkable achievement that also signified the moment when the definition of “oral design” came to fruition.

Geller simultaneously advocated for oral design in his lectures and began new experiments using the oral design logo.

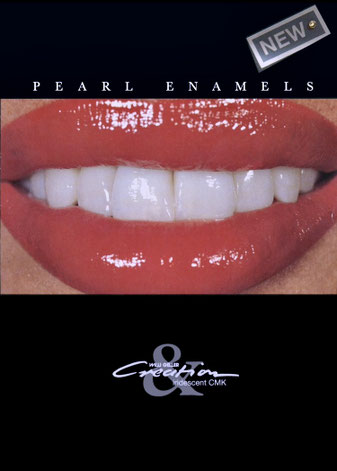

This involved revealing photographs during his lectures showing lips painted with red lipstick alongside metal-fired porcelain restorations fitted inside the oral cavity.

At that time, the mainstream lecture style focused solely on the know-how of fabricating metal-fired porcelain restorations, with little concern for whether the prosthetics matched the facial appearance and mouth area.

For women, applying lipstick to their lips is part of daily life, nothing special. Geller was the first to present those lipstick-coated lips during a lecture. That said, his lectures were by no means biased solely in that direction; he delivered academic content while incorporating such photographs to tighten up his presentation. The reason for presenting photos of lips with red lipstick during the lecture was, of course, to show the patient's facial appearance and the harmony of the mouth area. Furthermore, it added a touch of sexiness to the lecture, captivating the audience and preventing boredom during the long presentation. Above all, the success of this technique may have been that it created the association:

Red lips = oral design = Willi Geller

. Furthermore, looking at fashion magazines, it becomes clear that fashion professionals consciously incorporate such elements, recognizing them as essential. Therefore, Geller aimed not only for aesthetics but also to project fashionability through oral design. However, overdoing this fashion element risks obscuring the lecture's core message.

Geller carefully maintained this balance, delivering a solid lecture style throughout.

At the time, this method of presenting lectures using such photographs was not universally accepted, and some people expressed distaste. This stemmed from the belief that the photographs strayed from the academic focus, as well as from old-fashioned, rigid notions that they evoked sexual imagery.

However, this lecture method persists to this day. It is not limited to dental technicians; many dental professionals now employ this technique in their presentations. Times are changing, and they are catching up to Geller.

As an aside, the color films of Yasujiro Ozu, the world-renowned Japanese director, feature carefully calculated use of red. While I don't believe Willi Geller was influenced by Ozu, the effective use of red lips and the red in the oral design logo during his lecture demonstrates a similar technique that effectively impacts the audience.

While audiences tend to focus solely on Geller's provocative photographs, during his lecture he actively engaged international audiences by inserting images showing how he recreated the host country's flag by layering food coloring-tinted porcelain powder over metal coping.

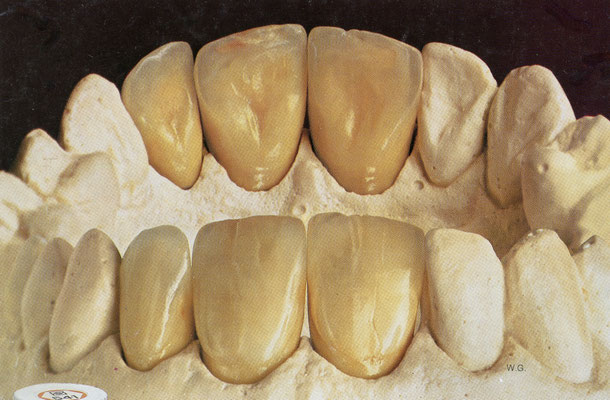

To jump ahead a bit, four years before Geller proposed oral design, in 1978, he produced a poster for Vita. This poster, featuring prosthetics created by Geller, bore the initials “W.G.” for the first time.It was just “W.G.” printed very small. In Europe, artists began signing their works slightly before the 13th century, when the Renaissance began.

During the preceding Gothic and Romanesque art periods, artists did not sign their works; they were merely craftsmen.

For dental technicians, even into the 20th century, their names remained unattributed. It was only when Geller added “W.G.” to his poster that dental technicians finally began having their names associated with their work and cases.

Why were the initials of the prosthesis maker necessary? Because someone had to start it someday.

Geller deliberately avoided complicating matters, simply placing the WG in the lower right corner of the photograph to pique people's interest.

Another purpose for including his initials on the prosthesis poster was to send a message to dental technicians and dentists, inspiring pride in the dental technician profession.

Even before advocating for “Oral Design,” Geller had already been a pioneer in such activities.

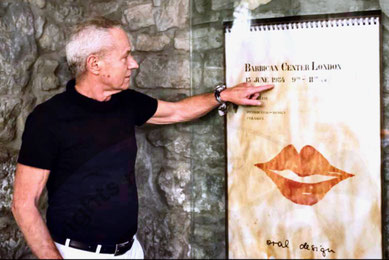

Geller created a new poster design for the 2nd International Symposium on Ceramics. At the time, the poster logo was made using lettering sheets (a type of sticker where you trace letters onto a film). He wrote the “Oral Design” logo and text, added illustrations, and sent it to the printer to be made into a large poster. Both large and small versions of the poster were produced. The large one was displayed at the venue, but he brought the small one home. While he was still alive, that poster was displayed in his dental laboratory.

Posters and Geller used at the 2nd Ceramic Symposium

oral design